Written by John Arcudi, Chris Warner, Anina Bennett, and Paul Guinan

Written by John Arcudi, Chris Warner, Anina Bennett, and Paul Guinan

Penciled by Dan Lawlis, Chris Warner, Mike Manley, Lee Moder, Andrew Robinson, and Robert Walker

Inked by Ian Akin, Ande Parks, Tim Bradstreet, Jim Royal, and Gary Martin

320 pages, color

Published by Dark Horse

I have to admit that I am really enjoying Dark Horse’s omnibus collections of their old Dark Horse Heroes line. It’s a strange trip down memory lane, bringing back characters that have mostly laid dormant for a decade. Even better, though, you can take a historical look at these stories, trying to puzzle through what did and didn’t work. In the case of the Barb Wire Omnibus, I can’t help but think that a better title for the collection would be The Rise and Fall of Barb Wire. It’s hard to not read this book and just be puzzled by some of the decisions made over the thirteen issues collected here.

Barbara Kopetski—better known around town as Barb Wire—is a local businesswoman in Steel Harbor, trying to run the Hammerhead Bar and Grill. With expenses continually rising, though, she’s forced to make a little extra cash by acting as a bounty hunter and pulling in those who have jumped bail or parole. And no matter how often she tries to stay away from the super-powered targets that would surely be tougher than her, somehow that seems to be all she’s going after.

Barbara Kopetski—better known around town as Barb Wire—is a local businesswoman in Steel Harbor, trying to run the Hammerhead Bar and Grill. With expenses continually rising, though, she’s forced to make a little extra cash by acting as a bounty hunter and pulling in those who have jumped bail or parole. And no matter how often she tries to stay away from the super-powered targets that would surely be tougher than her, somehow that seems to be all she’s going after.

The premise of Barb Wire was certainly a reasonable one; a tough, strong-willed woman taking down people who should have had the upper hand against her, but get out-maneuvered by Barb in the end. Reading the early issues of Barb Wire, it’s an entertaining enough read. John Arcudi (who wrote eight of the title’s original nine issues) has a good handle on the character; it’s hard to not like Barb even as she gets continually exasperated by all of the insanity that erupts around her. Making her the one level-headed person in Steel Harbor is a good hook for her character, and everything else falls into place from there. For the first five issues in particular, it’s a thoroughly enjoyable comic. I don’t think anyone would call it high art, but it’s easy to see why the attraction would be there to license the character for a film.

The problem is, though, it’s hard to not feel like Arcudi is forever getting sabotaged by other events happening elsewhere in the Dark Horse Heroes line. One storyline vanishes entirely after the third issue, as it turns out it was nothing more than a lead-in to the Will to Power crossover event at Dark Horse. (I’m actually a little surprised there wasn’t a footnote at the end of the third chapter in this collection instructing readers to check out the Dark Horse Heroes Omnibus Vol. 1 to find out what happened with Mace Blitzkreig’s latest attempt to take over Steel Harbor.) Additionally, the one interesting member of the supporting cast (The Machine) is written out after the fifth issue, to go star in what would turn out to be another series in the line that would be cancelled almost immediately after its debut.

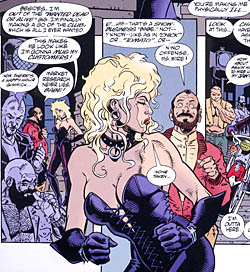

Then again, the art is pretty inconsistent in the original nine-issue run of Barb Wire as well. Dan Lawlis has the longest stretch with just four issues, but his exaggerated, curvy art is the best fit that Barb Wire ever got. Lawlis accentuates the shape of everyone’s bodies here; Barb may have rounded breasts and buttocks, but same is also true for how he draws male characters, with well-defined muscular torsos and thighs. It’s an equal-opportunity approach, and by the time he left I found myself genuinely sad to see him no longer drawing the book. Other approaches, like Lee Moder and Robert Walker, seem more restricted on just trying to draw hot women, but the best of the remaining artists on the original book is easily Mike Manley, who has probably the most realistic approach to the comic and certainly the least “hot” Barb Wire of them all.

Then again, the art is pretty inconsistent in the original nine-issue run of Barb Wire as well. Dan Lawlis has the longest stretch with just four issues, but his exaggerated, curvy art is the best fit that Barb Wire ever got. Lawlis accentuates the shape of everyone’s bodies here; Barb may have rounded breasts and buttocks, but same is also true for how he draws male characters, with well-defined muscular torsos and thighs. It’s an equal-opportunity approach, and by the time he left I found myself genuinely sad to see him no longer drawing the book. Other approaches, like Lee Moder and Robert Walker, seem more restricted on just trying to draw hot women, but the best of the remaining artists on the original book is easily Mike Manley, who has probably the most realistic approach to the comic and certainly the least “hot” Barb Wire of them all.

It’s also worth noting that while there are five different pencilers over the course of those original nine issues, Arcudi himself only writes the first eight issues. The conclusion is instead written by Anina Bennett and Paul Guinan, and it feels awkward and out of place with the rest of the series. I don’t know what happened to make Arcudi’s planned conclusion get thrown out, but what readers got instead is a bit of an insult. Barb Wire herself feels remarkably out of character, killing off a villain without even batting an eye. It was at that point that I realized that while Arcudi always made Steel Harbor feel like a very violent place, Barb Wire herself had never resorted to violence to fix a problem if there was another option available. It really made me appreciate Arcudi’s run that much more, and just cringe over the last-minute substitution of writers for the conclusion of the series.

The original Barb Wire comic was published from April 1994 to February 1995. In May 1996, the Barb Wire film hit theatres. Starring Pamela Anderson, the film is best known now for being a notorious flop. The film was savaged by critics for just about everything (including winning Anderson a Golden Raspberry for Worst New Star), and the property was declared toxic. You can imagine Dark Horse’s distress, then, that also released alongside the movie was Barb Wire: Ace of Spades, a four-issue mini-series meant to feed off the film’s success. Written and penciled by Chris Warner, Barb Wire was retooled to fit in more with the movie. The Hammerhead Bar and Grill had transformed from the small intimate bar to a massive hollowed out warehouse, and Barb herself has a new hair style and wardrobe to look more like Anderson. This all seems like a logical step to make fans of the movie happy, right?

The original Barb Wire comic was published from April 1994 to February 1995. In May 1996, the Barb Wire film hit theatres. Starring Pamela Anderson, the film is best known now for being a notorious flop. The film was savaged by critics for just about everything (including winning Anderson a Golden Raspberry for Worst New Star), and the property was declared toxic. You can imagine Dark Horse’s distress, then, that also released alongside the movie was Barb Wire: Ace of Spades, a four-issue mini-series meant to feed off the film’s success. Written and penciled by Chris Warner, Barb Wire was retooled to fit in more with the movie. The Hammerhead Bar and Grill had transformed from the small intimate bar to a massive hollowed out warehouse, and Barb herself has a new hair style and wardrobe to look more like Anderson. This all seems like a logical step to make fans of the movie happy, right?

What’s mystifying, then, is that people who saw the movie and wanted to see more would have probably hated Barb Wire: Ace of Spades. Apparently aiming to also make readers of the comic happy, Barb Wire: Ace of Spades still features super-powered characters like the Machine, Wolf Gang, and Mace Blitzkreig. Additionally, it also features the return of a villain from the original run of the comic (the Ace of Spades killer). In short, while the character and the visuals may look like the movie, the actual comic itself has no connection in the slightest. It makes you wonder why someone thought that the comic should try and make everyone happy, because the end result was sure to please neither camp. It certainly doesn’t help that the story itself is rather uninspired; perhaps Warner was unhappy with the changes he had to make to connect the comic to the film, but it’s a lackluster, uninteresting final outing for the character. If I’d been reading Barb Wire up until that point, I’d have been incredibly disappointed. Instead, I just found myself regularly pausing as I went through these last few chapters of the Barb Wire Omnibus, just wincing and shaking my head.

At the end of the day, Barb Wire feels almost like a cautionary tale, how a solid mid-level comic (Barb Wire as written and drawn by Arcudi and Lawlis) can be undercut by attempts to cater to company-wide crossovers, spin-offs, and related media projects. It’s a lesson that I think companies could still learn today, quite frankly. Look at the rise and fall of Barb Wire, and understand that this could just as easily happen to your own characters. You have been warned, publishers.

Purchase Links: Amazon.com