Written by Barbara Kesel, Jerry Prosser, Mike Richardson, Randy Stradley, Chris Warner

Written by Barbara Kesel, Jerry Prosser, Mike Richardson, Randy Stradley, Chris Warner

Art by various creators

488 pages, color

Published by Dark Horse

In 1993, it seemed like every publisher was debuting a new superhero line. The Image Comics explosion of the previous year had multiple companies putting together their own response; some took existing properties and tied them together, others launched entire new characters and titles. Dark Horse’s approach was Comics’ Greatest World, which was renamed Dark Horse Heroes a little over a year later. Now, with both the original 16-part mini-series as well as the later 12-part Will to Power crossover collected into a single omnibus, it’s interesting to look back and see both the strengths and the weaknesses of the line brought together so succinctly—as well as the fact that in many ways, it looks like nothing has really changed when it comes to a publisher launching a new line.

The original Comics’ Greatest World introduction was on the surface designed rather cleverly; with the universe divided up into four cities/regions, each month would debut a four-part weekly mini-series (cover priced at $1 each) that would introduce four characters or teams from that location. At the same time, one common thread would unite all 16 issues. It’s as early as the second week, though, where things began to fall apart. There were two big problems with the initial comics; first, a lack of 16 strong concepts to keep readers interested, and second, Dark Horse’s determination to have everything connect together. The lack of enough strong concepts shows up surprisingly quickly; after the vigilante X kicked off the entire project in the city of Arcadia in a tense first issue, the second installment had him go up against four people in matching featureless suits called the Pit Bulls, who had no discernable personalities and whose gimmick was that they all had names normally given to dogs and had orders shouted to them as if they were canines. You can see the problem, here. I remember some 15 years ago having already lost some interest thanks to this being the second chapter, and now it feels even weaker. It’s not the only time this happens, either—the Steel Harbor stories in particular are hamstrung by generic and dull superheroes in the Wolf Gang, and how someone thought the conclusion of the story involving a character named Motorhead who (after three issues of moaning, “I won’t release the power!”) shows up and blasts all the bad guys in the space of two pages… Well, it’s a little surprising. Every time another one- or zero-dimensional character shows up, the urge to stop reading intensifies.

More problematic, though, is the ongoing storyline about aliens trying to find a member of their own race called the Heretic. There are only so many times that someone can read about invisible aliens looking at a new character and noting that there are traces of the Heretic before one starts hoping that the aliens will fall into a black hole and leave you alone. People who remember the (more recent) launch of CrossGen’s shared universe will certainly be experiencing déjà vu, with the similarities between these aliens staring and analyzing and CrossGen’s superpowered overlords going around and granting magic sigils more than a little obvious. One gets the impression that CrossGen hadn’t learned from Dark Horse’s mistake; there are more people who will be turned off by this all-encompassing connection between the characters and locations than those who will find it an attraction.

This isn’t to say that the original mini-series didn’t have its strengths, though. Despite the inclusion of the Pit Bills, Jerry Prosser’s Arcadia is the most cohesive and interesting of the four, set in a city rife with corruption and one person responding in his own violent way. It’s no surprise to me that it spawned the two characters who lasted the longest in their own comics, X and Ghost. The former is a strange cross between DC Comics’s The Question and Marvel Comics’s The Punisher, but in a good way. The latter had the distinct advantage of being drawn by Adam Hughes, but also having enough of an air of mystery and intrigue about the character (as she tries to discover who killed her) to extend stories well. Of the others, Barbara Kesel’s Golden City is a little clichéd, but there’s a certain charm to her introduction of the “perfect” city where superheroes make a brighter tomorrow, even if the ending is telegraphed so badly you keep waiting for a twist that never happens. Chris Warner’s introduction of Barb Wire makes you forget the bad movie with Pamela Anderson, an impressive feat in its own right the more you think about it.

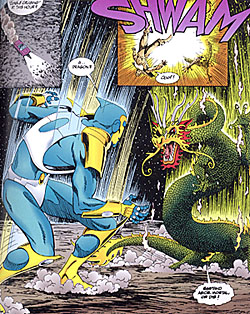

Randy Stradley’s first three segments of The Vortex are some of the best installments of the entire series. He’s able to keep things tense, really explore the strangeness of this part of the country, and it makes you wonder just why there weren’t successful Division 13, Hero Zero, and King Tiger series spun out of this. The latter two certainly helped in being drawn by Eric Shanower and then Paul Chadwick, but Stradley is able to not only shift genres effortlessly from one to the next (military prison break, to giant monster fights, to mystical warriors), but he actually brings a cohesiveness to the story that the others (especially Golden City and Steel Harbor) were lacking, avoiding the tired “a bad situation happens, and each chapter brings in a new character to swing a punch” route that we’d seen so much of.

Randy Stradley’s first three segments of The Vortex are some of the best installments of the entire series. He’s able to keep things tense, really explore the strangeness of this part of the country, and it makes you wonder just why there weren’t successful Division 13, Hero Zero, and King Tiger series spun out of this. The latter two certainly helped in being drawn by Eric Shanower and then Paul Chadwick, but Stradley is able to not only shift genres effortlessly from one to the next (military prison break, to giant monster fights, to mystical warriors), but he actually brings a cohesiveness to the story that the others (especially Golden City and Steel Harbor) were lacking, avoiding the tired “a bad situation happens, and each chapter brings in a new character to swing a punch” route that we’d seen so much of.

It’s hitting the halfway point of this omnibus that things begin to get a little strange. Before the reprinting of Will to Power begins, there’s an eight-page text summary explaining what happened in-between the two, primarily in the dull Out of the Vortex series, but in other series as well. Reading the summary manages to come across as uninteresting with just the high points being displayed, and it’s here that you see Dark Horse having taken a wrong turn entirely. By having the premiere title dealing with the “mysteries” of the connections between all of the series, it’s easy to see why the line was already starting to collapse. It’s actually an effort to read the summary, although it does warm my heart to know that fifteen years ago I’d made the right decision to quickly give up on Out of the Vortex. (It’s also rather telling that while bits of the summaries talk about what’s happening in titles set in Golden City and Steel Harbor, the X and Ghost titles had wisely stayed out of all of this nonsense.)

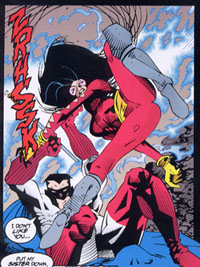

Will to Power itself is an extremely disjointed series, the idea being that the superhero Titan is manipulated by both the government and his former team leader Grace as his powers increase and he begins to rampage across the country, becoming more and more unstoppable with every page. (Not quite unlike Black Adam towards the end of DC Comics’s 52. The longer you’ve read “shared universe” comics, the more you realize that you’ve already seen everything.) Each of the original four writers revisit their locales, and some of the same strengths and weaknesses are once more on display. Prosser’s issues set in Arcadia don’t really feel like they belong in the same storyline as everything else to come, but it’s a strong beginning to the story, cleverly placing Titan’s childlike ideas of right-and-wrong opposite X’s jaded and cynical world view. Warner’s story set in Steel Harbor, on the other hand, is instantly forgettable (and is also plagued with the least competent art in the entire omnibus, unfortunately) and Kesel’s story is predictable and feels plodding. It once more comes down to Stradley to punch up the intensity, actually managing to make the man from the Vortex fighting Titan (plus an appearance by King Tiger) genuinely interesting. The more I read of Stradley’s contributions to the Dark Heroes Heroes omnibus, the more I couldn’t help but wonder why he hadn’t written more of the actual titles, because the end result might have been a lot better than what we got.

With Comics’ Greatest World, Mike Richardson wrote 1-page prologues detailing the arrival of the Heretic on Earth and his strange experiments, a back history to the universe. Here, Richardson along with artist Brian Apthorp use the prologue to give the untold story of Titan’s early life. And quite frankly, it doesn’t fit the rest of Will to Power in the slightest, with Will to Power‘s constant fight scenes and general “who can hit the hardest?” attitude. Here, it’s an uncomfortable story to read because you quickly realize that Titan is a pretty pathetic person. He’s someone who never got over the lack of approval from his father, and grew up a cringing, simpering person that can only hide behind a uniform in order to actually act. Add in a strange undertone of homoeroticism (between his desire to both be like and with his father, his fear and need for being around the high school boys, the sheer number of images involving men in their underwear in Titan’s memories, and Apthorp’s art in general providing a soft, stereotypically delicate look to Titan as a teen) and this is one of the more unusual secret origins for a character—especially with the epilogue involving the teenage version of Titan scolding the adult for having never been a real man and blaming everyone else for his problems. Honestly, it’s much more interesting to read over Warner or Kesel’s contributions, although I’m not sure how much more of “the pathetic adventures of Titan” one would really be able to take.

With Comics’ Greatest World, Mike Richardson wrote 1-page prologues detailing the arrival of the Heretic on Earth and his strange experiments, a back history to the universe. Here, Richardson along with artist Brian Apthorp use the prologue to give the untold story of Titan’s early life. And quite frankly, it doesn’t fit the rest of Will to Power in the slightest, with Will to Power‘s constant fight scenes and general “who can hit the hardest?” attitude. Here, it’s an uncomfortable story to read because you quickly realize that Titan is a pretty pathetic person. He’s someone who never got over the lack of approval from his father, and grew up a cringing, simpering person that can only hide behind a uniform in order to actually act. Add in a strange undertone of homoeroticism (between his desire to both be like and with his father, his fear and need for being around the high school boys, the sheer number of images involving men in their underwear in Titan’s memories, and Apthorp’s art in general providing a soft, stereotypically delicate look to Titan as a teen) and this is one of the more unusual secret origins for a character—especially with the epilogue involving the teenage version of Titan scolding the adult for having never been a real man and blaming everyone else for his problems. Honestly, it’s much more interesting to read over Warner or Kesel’s contributions, although I’m not sure how much more of “the pathetic adventures of Titan” one would really be able to take.

The art in the Dark Horse Heroes omnibus is extremely varied, to put it mildly. Adam Hughes is the one superstar on board, drawing the 15-page story introducing Ghost. With his typical good-girl art full of gentle curves and carefully rendered anatomy, it’s the most beautiful thing in the book by a long shot. That said, there are some other contributions that certainly stand out more than others. Ted Naifeh’s art for the chapter on the Machine is certainly unrecognizable to how he draws books like Courtney Crumrin these days, but still strong in its own right, a dark, dystopian style that transforms Steel Harbor into something out of a movie like Blade Runner. As mentioned earlier, Shanower and Chadwick both also provide great art for the book; Shanower’s delicate art that serves him so well in Age of Bronze channels a great combination of teen angst and Japanese monster movie excitement, while Chadwick does such a beautiful job illustrating King Tiger’s spells that it makes you wonder why more people haven’t asked him to draw this kind of book. And while I wasn’t that fond of Warner’s writing in the omnibus, his opening chapter to the book starring X and inked by Tim Bradstreet is just right for the story, a grim and gritty look that just reeks of corruption and intrigue.

The art in the Dark Horse Heroes omnibus is extremely varied, to put it mildly. Adam Hughes is the one superstar on board, drawing the 15-page story introducing Ghost. With his typical good-girl art full of gentle curves and carefully rendered anatomy, it’s the most beautiful thing in the book by a long shot. That said, there are some other contributions that certainly stand out more than others. Ted Naifeh’s art for the chapter on the Machine is certainly unrecognizable to how he draws books like Courtney Crumrin these days, but still strong in its own right, a dark, dystopian style that transforms Steel Harbor into something out of a movie like Blade Runner. As mentioned earlier, Shanower and Chadwick both also provide great art for the book; Shanower’s delicate art that serves him so well in Age of Bronze channels a great combination of teen angst and Japanese monster movie excitement, while Chadwick does such a beautiful job illustrating King Tiger’s spells that it makes you wonder why more people haven’t asked him to draw this kind of book. And while I wasn’t that fond of Warner’s writing in the omnibus, his opening chapter to the book starring X and inked by Tim Bradstreet is just right for the story, a grim and gritty look that just reeks of corruption and intrigue.

On the other hand, several of the contributions are a little lackluster. Paul Gulacy makes Barb Wire seem less capable than the script calls for, giving the primary impression of the character as being slutty (especially with her bikini top about ready to pop off at any given moment) rather than tough and someone to worry about. Than again, considering the other featured female character that shows up looks like she’s dressed for a gynecological exam instead of being a lawyer, at least Gulacy applied his misplaced taste across the board. More painful is all three Steel Harbor chapters of Will to Power looking like they were handed off to anyone who could draw quickly, regardless of quality. Tomm Coker at least went on to be much more accomplished, but you’d never know it here, the art looking more like sketch breakdowns instead of actually rendered art. Andrew Robinson and Jim Somverville, likewise, provide a cheap, rushed final product that is primarily devoid of background or any sort of visual oomph.

On the other hand, several of the contributions are a little lackluster. Paul Gulacy makes Barb Wire seem less capable than the script calls for, giving the primary impression of the character as being slutty (especially with her bikini top about ready to pop off at any given moment) rather than tough and someone to worry about. Than again, considering the other featured female character that shows up looks like she’s dressed for a gynecological exam instead of being a lawyer, at least Gulacy applied his misplaced taste across the board. More painful is all three Steel Harbor chapters of Will to Power looking like they were handed off to anyone who could draw quickly, regardless of quality. Tomm Coker at least went on to be much more accomplished, but you’d never know it here, the art looking more like sketch breakdowns instead of actually rendered art. Andrew Robinson and Jim Somverville, likewise, provide a cheap, rushed final product that is primarily devoid of background or any sort of visual oomph.

The Dark Horse Heroes Omnibus is, in the end, a fascinating historical footnote. You can see so much of what happened here get replicated elsewhere (Malibu’s Ultraverse, Malibu’s Protectorverse, DC’s constant rebooting of the Wildstorm Universe, the CrossGen line, and so on), and it’s really interesting to see all of this collected together. An X Omnibus is already planned, so hopefully we’ll get to see some other titles from the Dark Horse Heroes line show up in this way. As a reading experience, it’s more than a little disjointed, but every now and then you see sparks of greatness here—it’s a shame that as a whole it never lived up to some of its individual parts. For people who remember reading these comics 15 years ago, though, this might be a welcome trip down memory lane.

Purchase Links: Amazon.com