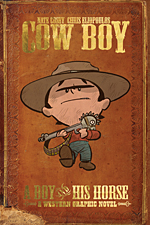

Written by Nate Cosby

Written by Nate Cosby

Art by Chris Eliopoulos

Additional stories by Roger Langridge, Brian Clevenger, Scott Wegener, Mitch Gerads, Colleen Coover, and Mike Maihack

96 pages, color

Published by Archaia

There are books that sneak up on you, and I’d put Cow Boy: A Boy and His Horse in that category. On its surface it looks like a cute kid’s book, with a 10-year old boy dressed up like a cowboy holding what looks like a toy gun. I challenge you to read this book, though, and not find yourself utterly captivated. Nate Cosby and Chris Eliopoulos have created a graphic novel that slowly but surely pulls you in, turning what at first appears to be a one-note joke into a deeply-affecting story about the bonds of family.

Coy Boy: A Boy and His Horse gives us Boyd Linney, a young boy who’s hunting down a series of criminals and turning them in for their bounty. At first, the gimmick seems simple: Boyd’s just 10 years old and his shotgun looks like a hobby horse. As he gruff-talks his way through the first town holding one of his targets, you find yourself chuckling along with Cosby’s script. Boyd talks like someone four times his age, with a gruff attitude and a no-holds-barred drive. Then you meet the first of the criminals that Boyd’s chasing after and the book takes a sudden turn to something holding a bit more drama than it initially seemed.

Cosby’s story for Cow Boy is one that gets progressively sadder despite the humor that surrounds individual moments within the script. (This is, after all, a comic where Boyd is able to sneak into a saloon keeper’s office by climbing inside a woman’s bustle.) As the initial reveal shows us, we’re reading a book about a situation so bad that a young boy has to hunt down and bring to justice his entire family. With each family member captured and hauled in, it becomes increasingly clear that Boyd is completely alone in the world, even though he’s just a kid who has a living family. Still, it’s hard not to laugh when, upon being asked if he’s going to cause a ruckus, little Boyd replies, "I do not. But the byproduct of my intentions could well lead to ruckus." He’s adorably cute even as he spits out lines that John Wayne would be proud of.

Cosby’s story for Cow Boy is one that gets progressively sadder despite the humor that surrounds individual moments within the script. (This is, after all, a comic where Boyd is able to sneak into a saloon keeper’s office by climbing inside a woman’s bustle.) As the initial reveal shows us, we’re reading a book about a situation so bad that a young boy has to hunt down and bring to justice his entire family. With each family member captured and hauled in, it becomes increasingly clear that Boyd is completely alone in the world, even though he’s just a kid who has a living family. Still, it’s hard not to laugh when, upon being asked if he’s going to cause a ruckus, little Boyd replies, "I do not. But the byproduct of my intentions could well lead to ruckus." He’s adorably cute even as he spits out lines that John Wayne would be proud of.

That cuteness is no small part thanks to Eliopoulos, whose art is probably best known from the all-ages Franklin Richards comics that Marvel used to publish. It’s a clean, jaunty style; little pools of black ink for eyes, a pert nose, small round mouth. Watching Boyd’s short stature struggling to clamber up onto a rocking chair is the sort of moment where you know that Eliopoulos is the right man for this job. Boyd is disarmingly cute, but he’s also immensely dangerous thanks to Eliopoulos. Don’t let that cuteness distract you, though; there’s also a lot of great storytelling. He knows when to focus on his main character, when to switch the viewpoint to a specific action (like a tight close-up on his hands loading shotgun shells while continuing to talk), and when to go for something entirely differently. It’s a good control of the visual look of the book, and I appreciate that Eliopoulos doesn’t use "all ages book" as an excuse for any short cuts.

There are four additional short stories included in Cow Boy: A Boy and His Horse by some strong creators (Roger Langridge, Brian Clevenger, Scott Wegener, Mitch Gerads, Colleen Coover, and Mike Maihack) and while I enjoyed all of them, I must admit that I’d have actually been happier without them. I adore new comics by people like Langridge or Coover, so to have me getting antsy between each chapter as we would temporarily cut away to a new two- or three-page story, that says a lot about how good a job that Cosby and Eliopoulos performed here. Cow Boy: A Boy and His Horse is one of my favorite comics of the year so far, easily. Highly recommended, and then some. I’m already on board for the sequel, whenever that might be.

Purchase Links: Amazon.com | Powell’s Books