By Moyoko Anno, Aurélia Aurita, Frédéric Boilet, Étienne Davodeau, Nicolas de Crécy, Emmanuel Guibert, Kazuichi Hanawa, Daisuke Igarashi, Little Fish, Taiyo Matsumoto, Fabrice Neaud, Benoît Peeters, David Prudhomme, François Schuiten, Joann Sfar, Kan Takahama, Jiro Taniguchi

By Moyoko Anno, Aurélia Aurita, Frédéric Boilet, Étienne Davodeau, Nicolas de Crécy, Emmanuel Guibert, Kazuichi Hanawa, Daisuke Igarashi, Little Fish, Taiyo Matsumoto, Fabrice Neaud, Benoît Peeters, David Prudhomme, François Schuiten, Joann Sfar, Kan Takahama, Jiro Taniguchi

256 pages, black and white

Published by Fanfare/Ponent Mon

I was delighted to recently pick up a copy of Japan as Viewed by 17 Creators; published several years ago, I’d heard nothing but praise for this collection of short stories by both Japanese and European comic creators, each set in a different location within Japan. It’s an ambitious, far-reaching project, with half of the creators flying over to Japan in order to learn about their assigned spot and then trying to convey its charms to the reader. What I found, though, was that some creators who I’d expected great things from didn’t quite hit the mark, while others surprised me with their strong contributions.

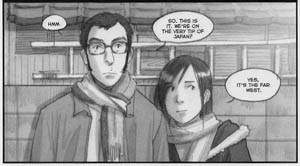

Japan as Viewed by 17 Creators starts on the western tip of the island nation, and slowly moves its way east and north across the country. While if nothing else it’s a logical progression of the stories, it works out doubly well because it means that Kan Takahama’s "At the Seaside" opens the book. Takahama tells her story in the form of guiding a journalist around the remote village of Amakusa, showing him her house and talking about her childhood of staring out at the ocean. "At the Seaside" is more than just a travelogue, though; it’s about the relationship between the two characters with one another. It’s a short but sweet story, and I love how Takahama draws her story with soft shaded pencils and a strong sense of scenery. Reading "At the Seaside" made me want to go to Amakusa myself, and it’s a sharp way to begin the book.

Japan as Viewed by 17 Creators starts on the western tip of the island nation, and slowly moves its way east and north across the country. While if nothing else it’s a logical progression of the stories, it works out doubly well because it means that Kan Takahama’s "At the Seaside" opens the book. Takahama tells her story in the form of guiding a journalist around the remote village of Amakusa, showing him her house and talking about her childhood of staring out at the ocean. "At the Seaside" is more than just a travelogue, though; it’s about the relationship between the two characters with one another. It’s a short but sweet story, and I love how Takahama draws her story with soft shaded pencils and a strong sense of scenery. Reading "At the Seaside" made me want to go to Amakusa myself, and it’s a sharp way to begin the book.

While I’d never seen Takahama’s comics before, some familiar creators also delivered with equal strength. Jiro Taniguchi’s works like The Walking Man and A Distant Neighborhood did such a strong job of wrapping narrative with location that his "Summer Sky" is unsurprisingly good. I appreciated that he was able to marry details about the past and present together here, talking about returning to a home town, the importance of family, and the young girl that has grown up in his absence. Taniguchi’s art is sharp and defined as always, with its thin delicate lines that carefully bring every last bit into focus. The same is also true of François Schuiten’s art; teamed up with his long-time collaborator Benoît Peeters, the two showcase a potential future Osaka in the form of a guidebook. In typical Schuiten form, massive futuristic buildings are married with greenery, and strange details like the evolution of the insect within Osaka are highlighted.

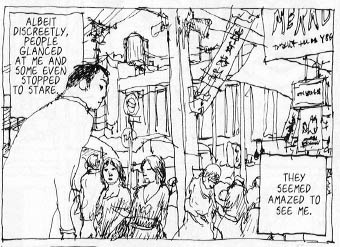

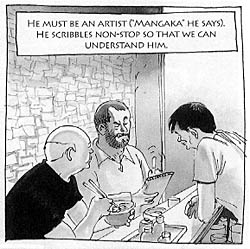

There’s more than enough strong material to entertain. Nicolas de Crécy sets "The New Gods" in Nagoya, using a loose, scribbly style of art to talk about Japan’s mascots and icons as deities. It’s a sharp idea that really brings to life a specific part of Japan’s culture, one that works doubly so by having it being narrated by a new "god" that has come to Japan in order to gain focus. It’s easily one of the best stories in the book, and de Crécy’s art helps seal the deal by bringing the streets and stores to life in a way that might initially seem rough, but in fact contains a surprising amount of detail and care in detailing this Japanese city. Aurélia Aurita’s "Now I Can Die!" takes a slightly different tactic as well, merging what at a glance seems like three different subjects (the Japanese group baths, a journey to a remote island lighthouse, and a romantic relationship) into one larger piece that all connect surprisingly well. Her art feels very childish and youthful, and I think that works in the story’s favor, imbuing it with a lot of energy and fun.

There’s more than enough strong material to entertain. Nicolas de Crécy sets "The New Gods" in Nagoya, using a loose, scribbly style of art to talk about Japan’s mascots and icons as deities. It’s a sharp idea that really brings to life a specific part of Japan’s culture, one that works doubly so by having it being narrated by a new "god" that has come to Japan in order to gain focus. It’s easily one of the best stories in the book, and de Crécy’s art helps seal the deal by bringing the streets and stores to life in a way that might initially seem rough, but in fact contains a surprising amount of detail and care in detailing this Japanese city. Aurélia Aurita’s "Now I Can Die!" takes a slightly different tactic as well, merging what at a glance seems like three different subjects (the Japanese group baths, a journey to a remote island lighthouse, and a romantic relationship) into one larger piece that all connect surprisingly well. Her art feels very childish and youthful, and I think that works in the story’s favor, imbuing it with a lot of energy and fun.

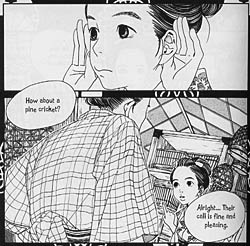

I was a little surprised to see that several creators set their stories in Japan’s past. Moyoko Anno’s "The Sound of Crickets" is little more than a vignette about the practice of keeping a caged cricket, but Anno’s art is beautiful, and there’s a lot of charm in its few, short pages. Taiyo Matsumoto’s "Kankichi" is wonderfully odd, something that shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone who’s read his other works like Tekkon Kinkreet or No. 5. It’s composed like a Japanese folk tale about a boy who grew up painting, and while it really does little to bring Kanagawa itself to life, its link to Japan’s fables is an important one. Daisuke Igarashi melds these last two approaches into one in "The Festival of the Bell-Horses," letting dreams and reality blend together in a way that showcases life in an earlier time, but also brings the fantastic briefly into the mix.

I was a little surprised to see that several creators set their stories in Japan’s past. Moyoko Anno’s "The Sound of Crickets" is little more than a vignette about the practice of keeping a caged cricket, but Anno’s art is beautiful, and there’s a lot of charm in its few, short pages. Taiyo Matsumoto’s "Kankichi" is wonderfully odd, something that shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone who’s read his other works like Tekkon Kinkreet or No. 5. It’s composed like a Japanese folk tale about a boy who grew up painting, and while it really does little to bring Kanagawa itself to life, its link to Japan’s fables is an important one. Daisuke Igarashi melds these last two approaches into one in "The Festival of the Bell-Horses," letting dreams and reality blend together in a way that showcases life in an earlier time, but also brings the fantastic briefly into the mix.

Some stories are stronger than others, though. David Prudhomme’s tale of shoes leaving the front entryway of a home and walking around town sounds better than the actual execution was. The same is also true of Emmanuel Guibert’s "Shin.Ichi," which marries text with spot illustrations in a story about friendship that seems to wish to be a Haruki Murakami short story but never quite connects. Joann Sfar’s story was also a bit of a disappointment, as he lets his friend Walteroo give the real lowdown on Tokyo. The idea isn’t bad, and some of the pieces of information about the idealized version of Tokyo versus the reality are interesting, but I never felt connected to Sfar’s narrator. Matched with some of the roughest Sfar art I think I’ve seen, it reminded me more of doodles dashed off into a sketchbook to be developed into something bigger down the road, but never quite got there.

Last but not least, there are some straight travelogue pieces that all work well. Fabrice Neaud’s "The City of Trees" is about Neaud’s trip to Sendai, but mixing details of his own life into his observations about Japan. The introductory paragraph about Neaud mentions frankness as a quality of Neaud’s work, and I have to agree. Nothing is hidden here, from boyfriend troubles to talking about how someone looks like Vermeer painting. His art has a beautiful grace to it, and I definitely would like to read more of Neaud’s journal comics. Kazuichi Hanawa’s story about hiking up a mountain brings to life his story of remote life in Japan, and while it doesn’t say much about Hanawa (unlike Neaud’s piece), it’s a pleasant story that shows a slightly different side of the country. Last but not least is Étienne Davodeau’s "Sapporo Fiction," which cleverly has it narrated by a Japanese man showing the slightly clueless Davodeau around Sapporo. Seeing Davodeau’s mistakes and triumphs through the eye of a local is a smart way to handle what might have otherwise been ordinary, and it’s a sweet way to end the book.

Last but not least, there are some straight travelogue pieces that all work well. Fabrice Neaud’s "The City of Trees" is about Neaud’s trip to Sendai, but mixing details of his own life into his observations about Japan. The introductory paragraph about Neaud mentions frankness as a quality of Neaud’s work, and I have to agree. Nothing is hidden here, from boyfriend troubles to talking about how someone looks like Vermeer painting. His art has a beautiful grace to it, and I definitely would like to read more of Neaud’s journal comics. Kazuichi Hanawa’s story about hiking up a mountain brings to life his story of remote life in Japan, and while it doesn’t say much about Hanawa (unlike Neaud’s piece), it’s a pleasant story that shows a slightly different side of the country. Last but not least is Étienne Davodeau’s "Sapporo Fiction," which cleverly has it narrated by a Japanese man showing the slightly clueless Davodeau around Sapporo. Seeing Davodeau’s mistakes and triumphs through the eye of a local is a smart way to handle what might have otherwise been ordinary, and it’s a sweet way to end the book.

Japan as Viewed by 17 Creators is a nice book, and I’m tickled at the idea of seeing Korea as Viewed by 12 Creators later this year as well. While like most anthologies the quality of contents goes up and down, there’s far more to recommend the book than not. And, by using creators both from within and outside of Japan, the mix of perspectives stays fresh and diverse. For those of us who can’t afford a real trip to Japan, this is a nice (temporary) substitute for the experience.

Purchase Links: Amazon.com | Powell’s Books