Written and drawn by Emmanuel Guibert

Written and drawn by Emmanuel Guibert

Photography by Didier Lefèvre

Design, color, and layout by Frédéric Lemercier

288 pages, color

Published by First Second Books

I’m a little mortified to admit that it’s taken me a couple of months to finally read The Photographer, the story of photojournalist Didier Lefèvre’s journey with Médecins Sans Frontièrs (Doctors Without Borders) into Afghanistan in 1986. It seemed like the kind of book that I couldn’t take lightly, that I wanted to reserve extra time to read. Finally, the rest of the world slowed down around me, and over the course of two days I dove into the book. What I found made me wish that somehow I could relive that initial experience of reading it all over again.

In 1986, the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan was still raging on and with no end in sight. That didn’t stop Médecins Sans Frontièrs (Doctors Without Borders), though, which continued to send humanitarian aid into a country that most of the world had abandoned. It was Didier Lefèvre’s first major assignment as a photojournalist, to accompany a group from Médecins Sans Frontièrs (MSF) as they traveled from Pakistan into Afghanistan. It seemed like a simple enough assignment, one that would net Lefèvre a series of amazing photographs. What it actually resulted in was a job that almost cost Lefèvre his life.

The Photographer was originally published as three separate volumes in France, and together they document the rise and fall of Lefèvre’s journey into Afghanistan. It’s not until I hit the end of the first book within The Photographer that I realized that what Emmanuel Guibert had managed to tell an engrossing story about a trip to Afghanistan where the entire first book is set in Pakistan. There’s so much in that initial third that needs to be told; the preparations both physically and mentally, learning about all of the different people from MSF that Lefèvre would travel with, and getting to know Lefèvre himself. After all, there were no flights into Afghanistan that they could take, their journey instead meaning a long trip on foot, sneaking across the border in the dark and evading Soviet helicopters that would shoot at anything moving. Guibert tells Lefèvre’s story effortlessly (not a surprise to anyone who’s also read Alan’s War, Guibert’s biography of World War II veteran Alan Cope), keeping the narrative flowing smoothly and enticingly. Vignettes along the way early on are intriguing—is the person he talked to a spy, a journalist, or something else?—and Guibert always places a high level of importance upon every story and experience of Lefèvre’s that he relates.

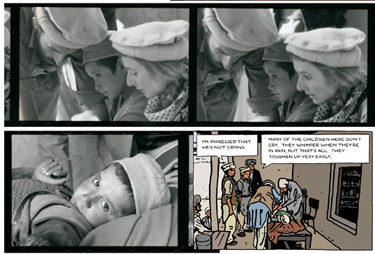

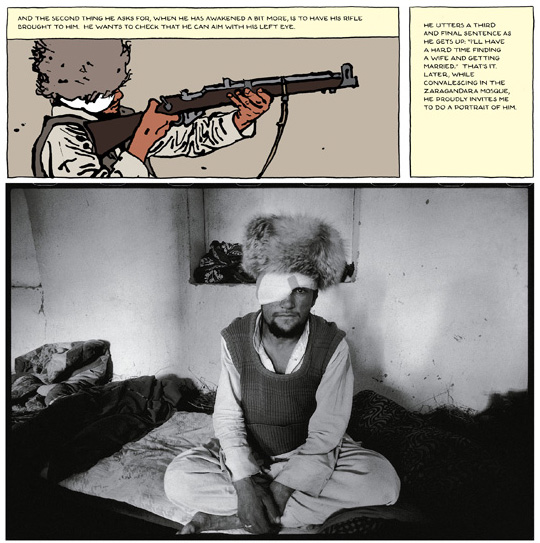

It’s not until you get to the second book, though, that you realize that things are only just starting to heat up. The second book opens with the entire team having to hide under blankets when a Soviet helicopter is sighted. Even a fingernail catching the sun could result in death—and it’s at this point that it begins to sink in just how precarious a situation Lefèvre and MSF are in. It’s an unflinching look at the results of the war, with Juliette and the rest of MSF treating the injured as they arrive at each new town. I’ll admit that I was slightly unprepared for some of the sights in The Photographer; the number of children who were hurt by bullets, shrapnel, or land mines was heartrending, and there’s one moment where you see the rather graphic aftermath of an explosion where a young boy’s lower jaw is completely gone. (I found myself relieved to get to the end of the book and discover the after word explaining what happened to him as well as a few other of the patients.) It’s not all shock and horror, though. Lefèvre gets to know many of the Afghani people throughout his journey, and it’s hard to not warm to many of them. The Photographer is as much a portrait of 1986 Afghanistan as it is Lefèvre and the MSF mission, and it helps put a face on the people.

It’s not until you get to the second book, though, that you realize that things are only just starting to heat up. The second book opens with the entire team having to hide under blankets when a Soviet helicopter is sighted. Even a fingernail catching the sun could result in death—and it’s at this point that it begins to sink in just how precarious a situation Lefèvre and MSF are in. It’s an unflinching look at the results of the war, with Juliette and the rest of MSF treating the injured as they arrive at each new town. I’ll admit that I was slightly unprepared for some of the sights in The Photographer; the number of children who were hurt by bullets, shrapnel, or land mines was heartrending, and there’s one moment where you see the rather graphic aftermath of an explosion where a young boy’s lower jaw is completely gone. (I found myself relieved to get to the end of the book and discover the after word explaining what happened to him as well as a few other of the patients.) It’s not all shock and horror, though. Lefèvre gets to know many of the Afghani people throughout his journey, and it’s hard to not warm to many of them. The Photographer is as much a portrait of 1986 Afghanistan as it is Lefèvre and the MSF mission, and it helps put a face on the people.

What goes up must come down, though, and the last volume of The Photographer details Lefèvre’s precarious journey back towards Pakistan, when he decides to journey back with a caravan instead of MSF so that he could get home a week sooner. It’s a harrowing travelogue, and Guibert brings to life Lefèvre’s despair and fear as things steadily go from bad to worse. What impressed me was that Guibert and Lefèvre don’t sugar-coat Lefèvre’s decisions and actions in this portion. There’s no singular person who’s at fault here, but some of the bad moves are certainly on the part of Lefèvre, and the book doesn’t flinch away from that honest portrayal. Without giving away many of the events of this portion of The Photographer, Guibert successfully gets the narrative into Lefèvre’s head here when things hit their all-time lowest, and it’s certainly the most emotional and scary moment of the entire book.

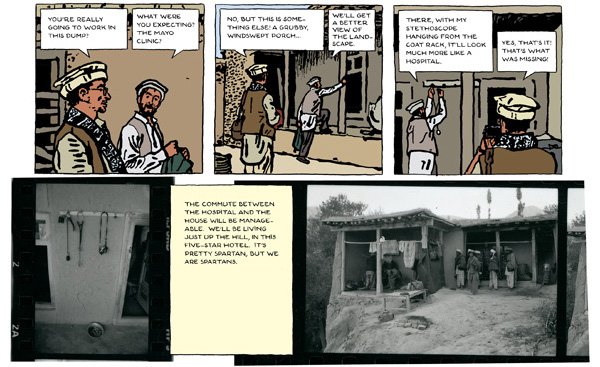

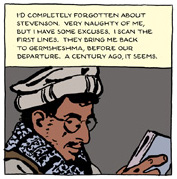

The Photographer is a combination of Lefèvre’s photographs and Guibert’s line art, and the two sync up much better than I’d have expected. Lefèvre’s photographs are reproduced in numerous sizes and dimensions; sometimes it’s a stream of images serving to show the passage of time, with dozens of snapshots over a single event or at times a stretch of the journey. At other moments it’s just one or two photographs dominating a page, letting the impact of coming across the grave of an MSF member from a previous trip, or part of the team in a precarious position in the river.  Guibert’s art matches up effortlessly with Lefèvre’s photographs. It’s as if you’re seeing additional, lost photographs of the trip that were transformed into art (even though it’s clear that these are not), with a high level of realism and connection to the photographs of Lefèvre. In the portions of the journey where Lefèvre took little or no photographs for various reasons, it’s the art that has to carry the narrative, and Guibert does that with the greatest of ease. Frédéric Lemercier is given a cover credit for his work on the layout and design of The Photographer, and once you’ve read the book you can see why. This book wouldn’t have worked if the two hadn’t integrated with each other perfectly, and Lemercier does an excellent job of providing just that.

Guibert’s art matches up effortlessly with Lefèvre’s photographs. It’s as if you’re seeing additional, lost photographs of the trip that were transformed into art (even though it’s clear that these are not), with a high level of realism and connection to the photographs of Lefèvre. In the portions of the journey where Lefèvre took little or no photographs for various reasons, it’s the art that has to carry the narrative, and Guibert does that with the greatest of ease. Frédéric Lemercier is given a cover credit for his work on the layout and design of The Photographer, and once you’ve read the book you can see why. This book wouldn’t have worked if the two hadn’t integrated with each other perfectly, and Lemercier does an excellent job of providing just that.

The Photographer is an amazing book. Alan’s War had told me that Guibert had a talent for biography, and The Photographer reinforces that statement. It’s hard to not come out of the book feeling slightly changed, as Lefèvre and Guibert expand the boundaries of your world. I will probably never go to Afghanistan, but The Photographer has given me an empathy for the region that I otherwise might have lacked. One of the best books of the year, by far, everyone with an interest in the world around them owes it to themselves to read this book. Highly recommended.

Purchase Links: Amazon.com | Powell’s Books