By Mira Friedmann, Batia Kolton, Rutu Modan, Yirmi Pinkus, David Polonsky, and Itzik Rennert

By Mira Friedmann, Batia Kolton, Rutu Modan, Yirmi Pinkus, David Polonsky, and Itzik Rennert

144 pages, color

Published by Actus Independent Comics; distributed by Top Shelf Productions

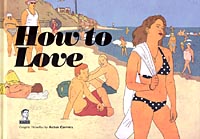

There are some books that are really worth waiting for, and high among them is a new release from the Actus Independent Comics collective. A collective of Israeli comic artists, you never know what you’re going to find from them. It could be a box of miniature comics, maybe an anthology of stories all written by Etgar Keret, or comics where everyone’s protagonist is named Victor. I think they’re at their best, though, when they all work off a theme; their Happy End book really showed a wealth of ways to tackle that idea, and their new book How to Love shows a really varied group of attacks on just that.

How to Love opens with Batia Kolton’s “Summer Story”—probably one of the most straightforward stories in the book. Dorit and her best friend love to spy on Dorit’s pretty neighbor kissing her boyfriend. Then Dorit’s neighbor comes along for a trip to the beach, and Dorit gets to see an entirely different side to her neighbor. Kolton plays out the neighbor’s role in “Summer Story” perfectly, with the deliberately unnamed woman using people around her to achieve her own goals, and Dorit being too starstruck with her neighbor to recognize what’s happening. Dorit’s hero worship and her neighbor’s self-obsession are the real loves of the story here, and it’s a fun, sharp little piece with humor happening on the sidelines to keep everything moving smoothly.

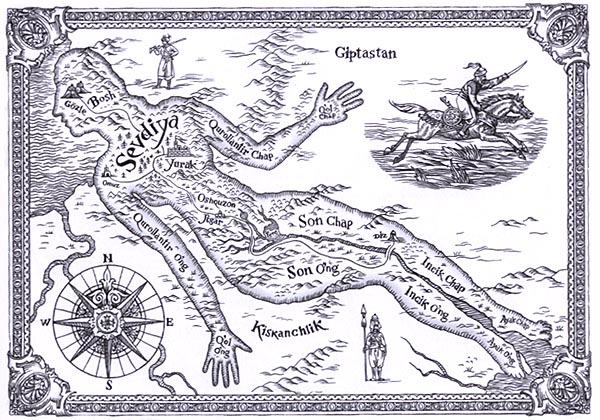

David Polonsky is a new name to me but his “L’Elixir D’Amour” is nothing what I was expecting, in a good way. It’s a series of illustrations on the right-hand side of the book, with narration on the facing pages as the Baron tells his paramour all about love. It makes me wonder which came first here; Polonsky’s crazy drawings that he then tried to match a story of love to, or if it was the ideas themselves that inspired the drawing. Either way, the result is really strong, with the text and illustrations each only half of the puzzle, unable to work without its other half. The ideas are outlandish and wonderful, from an Asiatic ruler who changed the boundaries of his country to match the contours of his wife’s body, to a country where flowers make their way towards bees instead of the other way around. “L’Elixir D’Amour” doesn’t overstay its welcome, staying just short enough that it remains feeling fresh and clever. Polonsky’s illustrations feel soft and beautiful here, no matter what the subject, and I really want to see more from him and soon.

Mira Friedmann’s “Independence Day” is set in the spring of 1966, when the West Bank and East Jerusalem were still occupied by Jordan. Nili is in love with her schoolmate Benny, and impulsively decides to be like one of the boys who occasionally sneak across the border into Jordan and steal something. When Nili is caught, though, things could quite possibly end badly for Nili—or is the worst still yet to come? Friedmann’s story at first seems pretty unremarkable save for its setting; the events that are unfolding seem more than a little cliché and predictable, and it’s hard to imagine anyone being surprised by it. “Independence Day” gets its saving grace by the last two pages of the story, which add a sharp sting to Nili’s story. Add to that Friedmann’s beautiful artistic style bringing that last panel to life, with the one liquid spilling into the other in a beautiful red-on-blue look, and it’s a strong ending to the story. While I didn’t dislike “Independence Day” I must say that it’s the closest How to Love comes to there being a weak link.

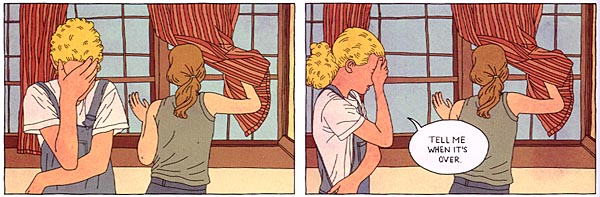

On the other hand, Itzik Rennert’s “Love Love Love” is a really strange experiment that at first seemed to be a failure, but ultimately worked far better than I could have imagined. Like Polonsky, Rennert’s story involves spot illustrations next to pieces of text, although both here are on the same page. Rennert has written a series of vignettes about his protagonist and his attempts at love and burgeoning desire. His (also nameless) protagonist’s travails are remarkably funny but at the same time, the further it progresses the more you can see an underlying sadness in his story. There’s a scene about halfway through where he visits a psychiatrist who tells him that he doesn’t love himself; the story then shifts to humor (as the protagonist tries out transference of love on the psychiatrist and his family) but it’s a moment that really sticks out the further you progress into “Love Love Love.” Rennert circuitously comes back to it as well, with the protagonist trying to list things that he does like, and as the story starts to lapse into an almost frightened desperation on the protagonist’s part, the sudden ending comes as both surprising and also believable. It’s a good conclusion, and one in which Rennert writes it almost as poetry. While Rennert’s writing is strong here, though, I have to say that I was disappointed with the art. It’s almost an afterthought here, completely unnecessary for accompanying the story, although some illustrations are certainly better than others. After Polonsky’s story requiring both story and art to work together, the casual, unnecessary nature of Rennert’s here is certainly not up to snuff.

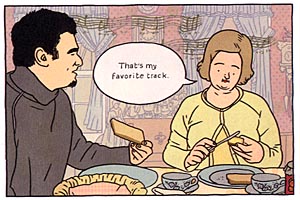

I was pleased to see that after the commercial and critical success of Rutu Modan’s Exit Wounds, she’s still creating short stories for Actus. “Your Number One Fan” is about Shabtai, who has received an offer to perform his music at a cultural center in Sheffield, England. It’s the big break he’s been waiting for, the chance to get his music played outside of Israel. “Your Number One Fan” contains just the right level of confusion and disturbing moments that it’s hard to not have it grab your attention. Modan’s protagonist is the kind of person that you can both sympathize and loathe, which is an impressive feat. It’s probably also the story that’s the farthest away from the general idea of love, although one can still see Modan’s connection to the theme pretty easily. Just like Rennert and Friedmann, Modan completely nails the ending of her story, giving it a nasty punch that stuck with me; the actual moment is a bit of a groaner, but based on what we know about the characters at that point, it has an unsettling, sad and pathetic air about it that Modan evokes perfectly.

I was pleased to see that after the commercial and critical success of Rutu Modan’s Exit Wounds, she’s still creating short stories for Actus. “Your Number One Fan” is about Shabtai, who has received an offer to perform his music at a cultural center in Sheffield, England. It’s the big break he’s been waiting for, the chance to get his music played outside of Israel. “Your Number One Fan” contains just the right level of confusion and disturbing moments that it’s hard to not have it grab your attention. Modan’s protagonist is the kind of person that you can both sympathize and loathe, which is an impressive feat. It’s probably also the story that’s the farthest away from the general idea of love, although one can still see Modan’s connection to the theme pretty easily. Just like Rennert and Friedmann, Modan completely nails the ending of her story, giving it a nasty punch that stuck with me; the actual moment is a bit of a groaner, but based on what we know about the characters at that point, it has an unsettling, sad and pathetic air about it that Modan evokes perfectly.

Last but not least is Yirmi Pinkus’s “8:00 to 10:00″—a simple story about a man in love and him working as the world moves on around him. There’s no surprise ending, no sudden reveal that will make you gasp, no strange twist. Pinkus’s story is exactly what it looks to be on the surface, but you know what? It’s also the sweetest piece in the book, a great way to end How to Love. There are some great visual touches here, like sound blasting out of the alarm clock like fire, or our protagonist wandering through his flowers as he waters them. If there had to be a soft, sentimental piece in How to Love, this is the way to do it. It’s probably the most forgettable story in the book because of its lack of additional layers, but Pinkus’s unapologetic style of his story makes that all right.

Last but not least is Yirmi Pinkus’s “8:00 to 10:00″—a simple story about a man in love and him working as the world moves on around him. There’s no surprise ending, no sudden reveal that will make you gasp, no strange twist. Pinkus’s story is exactly what it looks to be on the surface, but you know what? It’s also the sweetest piece in the book, a great way to end How to Love. There are some great visual touches here, like sound blasting out of the alarm clock like fire, or our protagonist wandering through his flowers as he waters them. If there had to be a soft, sentimental piece in How to Love, this is the way to do it. It’s probably the most forgettable story in the book because of its lack of additional layers, but Pinkus’s unapologetic style of his story makes that all right.

How to Love is printed in a handsome hardcover, landscape format. Each artist uses this format to their advantage, arranging their pages in a way that lets them provide “widescreen” tableaus, or numerous vertical panels placed next to each other. It’s an attractive book, and one that will definitely be sitting on my already-crowded bookshelves for many years to come. I’d say this is one of the Actus group’s strongest efforts yet; the three-year wait between their previous project and this is something that I’m willing to have happen again if we’re going to get such a great end result. How to Love hits stores in August 2008, and is worth your wait as well.